With the recent release of the feature film The Theory of Everything I was reminded of an extraordinary period in my life when I wrote a book about Stephen Hawking.

To start at the beginning, I must go back to 1973 when I returned from the USA to London with my wife and three boys and took a position teaching physics at the American School in London. There, each morning I found bright students – mostly American – anxious to hear me elucidate on the most fundamental of all the sciences.

I was fortunate to be able to teach two very different courses – one, an exam course called Advanced Placement for students who already knew they were going to study physical science at university and another course designed by Harvard University titled Project Physics. The latter focused on the most important discoveries from the time of the Greeks to the present day and was clearly something new. The syllabus consisted of topics which would appeal to anyone interested in the physical ideas which have shaped our world. These included astronomy as well as the usual concepts such as motion, heat, electricity, magnetism, light and the atom.

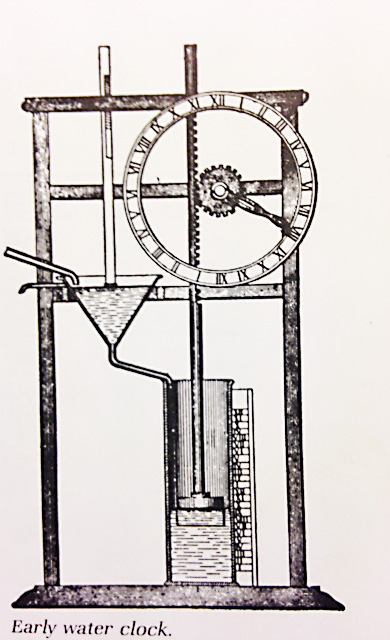

The course materials were rich and varied and allowed the instructor to improvise a great deal, in many cases using unique methods of the original investigators, such as Galileo’s use of a water clock  in his experiments on motion. This was a great opportunity for me to indulge my interest in the history of physics and astronomy, elaborating on the exciting work of some of my heroes such as Johannes Kepler, Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi. During that time I developed a reputation as being quite a good teacher: stimulating, interesting and committed to my students.

in his experiments on motion. This was a great opportunity for me to indulge my interest in the history of physics and astronomy, elaborating on the exciting work of some of my heroes such as Johannes Kepler, Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi. During that time I developed a reputation as being quite a good teacher: stimulating, interesting and committed to my students.

As a result of the success of teaching this course, I was inspired to prepare a lecture on a certain aspect of Einstein’s work and visit the United States to commemorate his 100th birthday in March of 1979. I was particularly interested in developing a multimedia presentation about the somewhat surprising fact that Einstein’s Nobel Prize was awarded, not for his revolutionary work in Relativity but, for the work he did on light – describing it as radiation formed of corpuscular bits of energy which was absorbed and emitted only in well-defined units which later became known as photons.

Prize from Max Planck

My lecture, which included recordings and photographs of Einstein and his colleagues, was very well received at the University of Pennsylvania, Amherst, MIT, Chicago, and Stanford. At the end of the trip, I returned to Europe via Switzerland to visit certain places associated with Einstein’s early life. Whilst there I discovered that a ceremony was about to be held in Berne as part of the centenary celebrations at which the very prestigious Albert Einstein Medal was being awarded. Naturally, I had to attend.

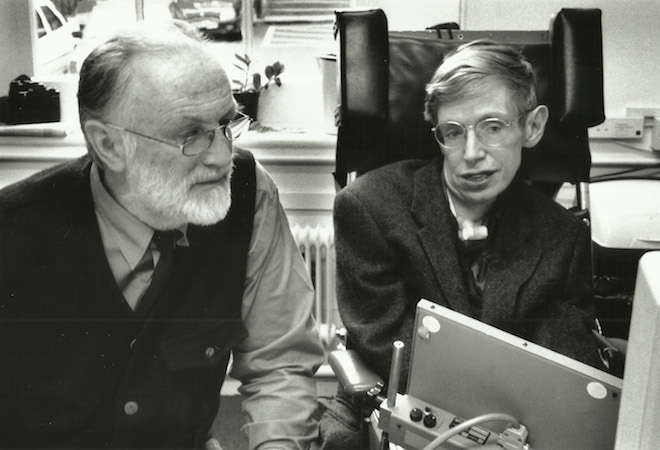

Arriving at the venue in Berne, I realised I was in a somewhat special audience and celebrating a special scientist. As I read the program notes, I soon realised the famous award was being given to an unusual physicist. The 1979 recipient of the Albert Einstein Award for ‘outstanding work in fundamental physics’ was a Cambridge University Professor named Stephen William Hawking. This was the first time I had ever seen or even heard of Hawking and I was somewhat shocked to see that he was bound to a wheelchair. As he was wheeled across the stage to accept the award, I was quite moved that a man so severely disabled could have achieved so much. I was not the only one so moved. As I scanned the auditorium that evening, I noticed that dozens of grown men and women: physicists, astronomers, journalists and other dignitaries, had tears in their eyes as Hawking mumbled his acceptance speech into a microphone.

15 Years Later . . .

Quite out of the blue fifteen years later, in the spring of 1994, I received a phone call from Richard Appignanesi of Icon Books. He had authored the first books (Freud and Lenin) in the popular series of Beginners Guides published by Icon and was now the commissioning  editor of the series. He asked if I would meet him for a beer the next day at a pub in Highgate, North London to discuss the possibility of writing something for the series. I accepted the invitation with great enthusiasm and met Appignanesi the next day to find out that he wished me to write a book on the Big Bang for Beginners. I agreed at once and my head was spinning with enthusiasm.

editor of the series. He asked if I would meet him for a beer the next day at a pub in Highgate, North London to discuss the possibility of writing something for the series. I accepted the invitation with great enthusiasm and met Appignanesi the next day to find out that he wished me to write a book on the Big Bang for Beginners. I agreed at once and my head was spinning with enthusiasm.

However, the very next day he rang again to ask if I would consider a slight change in the topic of the book. Rather than write about the Big Bang theory, he wished to know if I could handle a book about Stephen Hawking instead. Hiding my skepticism rather carefully, I again agreed enthusiastically and began to wonder if I could count on the Hawking’s cooperation since by this time he had become a celebrity. I started to get slightly nervous since I knew little of the details of Hawking’s work and nearly nothing of his life, except that he had a serious medical problem known to me as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain. Without much thinking, I decided to go right to the man and see whether he appreciated the idea of a book in this series about his life and work. I looked up the details of his address at Cambridge University and send him a fax.

Professor Stephen W. Hawking

Dept of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics

Cambridge University

Dear Professor Hawking,

I have recently been asked to write a book about yourself and your work in the popular ‘Beginners’ series published by Icon Books. I would like to know what you think of the idea and whether I could count on your cooperation on this project.

Yours Faithfully,

J.P.McEvoy PhD

London

Two days later I received a reply from Hawking’s administrative assistant Sue Masey instructing me to contact Professor Dennis Sciama at Oxford to talk about the book. Ms. Masey sent me Sciama’s contact details and after a congenial phone call, I was on my way to meet him in Oxford.

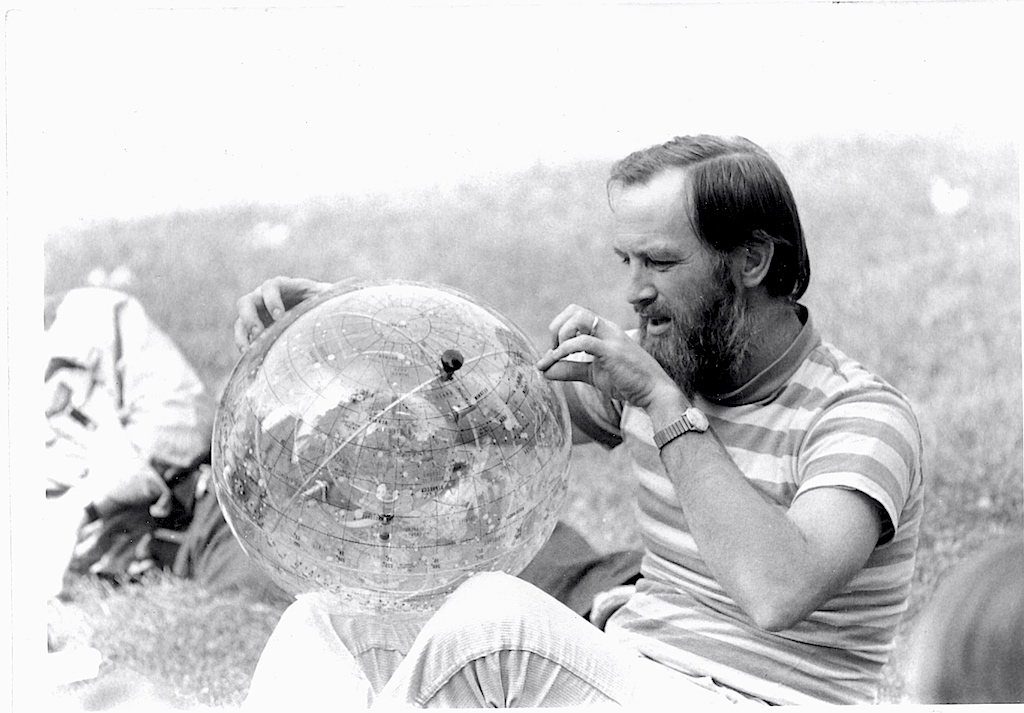

I was able to look up something about Sciama quite quickly. He had done his PhD at Cambridge just after the war where he was a student of the legendary Paul Dirac, one of the founders of Quantum Theory. He became active in work on cosmology and was very much interested in a fundamental concept involving motion, called Mach’s Principle. He was also an early proponent of the Steady State Theory of the Universe which he later rejected when the evidence from radio astronomy was known. He spent some time in the US at Harvard and Cornell and for a short time held a position at the very prestigious Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton where he met Einstein, who had also been concerned with Mach’s Principle.

As professor in his own right at Cambridge before coming to Oxford, Sciama had developed a reputation there for being an unselfish and helpful thesis advisor. For example, he never insisted on co-authoring the important papers that his students wrote as is common practice. His students included such outstanding PhD candidates as George Ellis, who became a professor of Physics in South Africa; Brandon Carter who became Director of Research at Paris Observatory; Martin Rees who went on to be the Astronomer Royal; and, none other than Stephen Hawking, the subject of our meeting. At the time I met him Sciama was himself an important researcher in the field of Relativistic Cosmology.

We met in the garden of Sciama’s house in the university town and spoke for over two hours as I remember. We talked about basic ideas in physics and some of the great discoveries of the 20th century. At that time I didn’t know a great deal about Hawking’s work but did know quite a bit from my teaching experience about the fundamentals of our field and how the great break throughs in physics and astronomy came about. I was very impressed with the polite manner and kind demeanour of Sciama and felt confident that he appreciated my ability to handle the assignment, that is, the Beginners book. Fortunately, he is one of those advanced thinkers who believes theoretical physicists should be able to explain their ideas in a simple straight-forward way. Thus, he was somewhat sympathetic to the idea of a popular book about such esoteric concepts as black holes.

As I left Oxford that day, speeding along the M40 back to London, I couldn’t help hearing in my head the immortal words of John Lennon after the Beatles last public performance on the rooftop of Apple Records . . .

I hope I passed the audition.

Only a few days later, I received a fax from Hawking’s office stating that he would be willing to cooperate with me on the book and I should make an appointment to come to Cambridge to see him. The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

Stephen Hawking for Beginners has sold thousands of copies around the world and has been translated into a dozen languages. The same book (unedited) is now sold under a new title as Introducing Stephen Hawking A Graphic Guide and is available from Amazon at http://www.amazon.co.uk/Introducing-Stephen-Hawking-Graphic-Guide/dp/1848310943 as a paperback and a Kindle Edition.

Wow, marvelous blog structure! How long have you ever

been blogging for? you made blogging glance easy. The

total glance of your web site is great, let alone tthe content material!

Dr. McEvoy,

To borrow a line from The Big Chill, “a long time ago we knew each other for a short period of time.” But, you made a difference.

I was one of your many students in AP Physics at ASL. While it must seem odd to many outsiders, I completely enjoyed Physics class! Looking back, I know one of the biggest reasons was you. You were terrifically entertaining and inspiring. So much so, I went on to major in Physics at Fairfield University, which prepared me well for a career as an engineer with an aerospace company. My college friends and I declared with own motto, which we still embrace decades later, “It’s all physics!”

My career has taken some shifts, the typical twists and luckily afforded some travel. I have returned to ASL and London a few times, traveled in Europe as often as I can, and fallen in love in Italy with my wife. When I recently traveled to France with my own children, I found myself reminiscing and endlessly excited to be sharing with them. Like you, I believe travel is truly educational. I will always be envious of your job as a travel agent/manager!

If I am truly lucky, perhaps I will be able to thank you in person – somewhere in this wonderful world.

T H A N K you.

P.S. Keep writing!

Guy,

Nice words from someone who has had experiences like my own.

I sincerely hope we do meet some time in the future.

Joe McEvoy

Dave,

You ‘ole smoothie!

I miss you guys terribly and am so pleased you are planning an extended trip to Old Blighty.

Bring another painting for our walls in Broadstairs. Pat is now doing water colours down there so we are blessed with the potential of our own gallery by the sea.

Joe

Joe, Mary and I love our copy of this book and cherish the moments when we’ve been in the company of your wonderful Irish-tales-perspectives. I heartily concur with Laura’s lament about the absence the profession felt once you took the different directions your heart and mind led you in life. I have many times told colleagues that the most impressive, effective and best teacher I ever had the pleasure to work with was you when we also shared the women’s and men’s basketball coaching responsibilities. Til our next crossing of paths.

And then even more years later …. Einstein’s grandsons also went to ASL and Craig was in my class. He was a real character and someone I will never forget!

This year for My New Year’s “Resolution” word I chose Light! I have been experimenting with how I can get more light into my life and have also decided to learn about stars and constellations. I have recently spent a lot of time in Scotland and have been amazed at the brilliance of their sky. Being able to see so many stars has inspired me to study them in a totally innocent and immature way . I hope to incorporate them into some form of art work. Anyway I was further inspired by what you have written about light and am now thinking of it from a “universal” and more scientific point of view.

I can see how easily you must have inspired so many students with even just a few words and so many first hand experiences! To have been in your classes must have been a very special and fortunate experience for all those ASL students ! I wish you were still there to continue to explain the practically unexplainable in the easy manner that you have… What a loss for all those there now !

And thanks for giving me another way to think of LIGHT…. Just bringing Craig Einstein to my mind again has been “enlightening” and helped me to consider many forgotten aspects of myself! Lol

Bring on the lights and lots and lots of STARS.

Reblogged this on joelzmcevoy.

You are a truly gifted and amazing man ! Great book too ! 🙂

A great story well told by an extraordinary man and friend……