In the Eternal City, physicist J.P. McEvoy reminisces about the Italian Enrico Fermi and visits an unusual artefact of the nuclear age.

On the day John Kennedy was shot in 1963, I was busy as a young physicist on a neutron scattering experiment at the RCA Sarnoff Research Laboratories in Princeton, New Jersey. I am sure of this because the news that day made an indelible mark on my imagination, as it did on most of my generation.

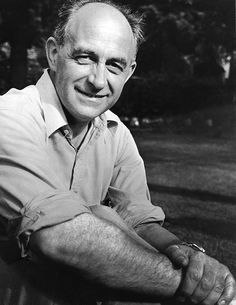

Since that time, I have since given up physics research and the idealism I had in the 1960s, but the fascination with the elusive subatomic particle, the neutron, has stayed with me for years due to its importance to the work of one man, the Italian Enrico Fermi. The least known of the giants of 20th century science – at least in the non-scientific community, Fermi’s work is so fundamental and influential to the major technological developments of mid-20th century physics that if anyone warrants the title ‘Father of the Atomic Age’, it must be Fermi. He almost single-handedly built the first self-sustaining nuclear reactor at Chicago in 1942 and was the head of an important theoretical group of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos which resulted in the first atomic bomb in 1945.

Yet Fermi did not attract publicity, having no time for such frivolous activity and processing such an ordinary, everyday persona. One story which sums up his attitude towards his self-importance is told about his attempt to cross the wide Via Foro during one of Mussolini’s demonstrations in the 1930s. Confronted by the carabinieri and told he couldn’t cross until the parade was finished, Fermi told the police it was urgent as he was Professor Fermi’s driver, knowing the truth would not be believed as he was dressed in his usual khaki pants and sweatshirt.

In December 1992, the University of Chicago certainly tried to change this image by celebrating the 50th anniversary of the first nuclear chain reaction which Fermi achieved on the campus in a converted squash court under the grandstands of Alonzo Stagg Field. I was there for the celebration.

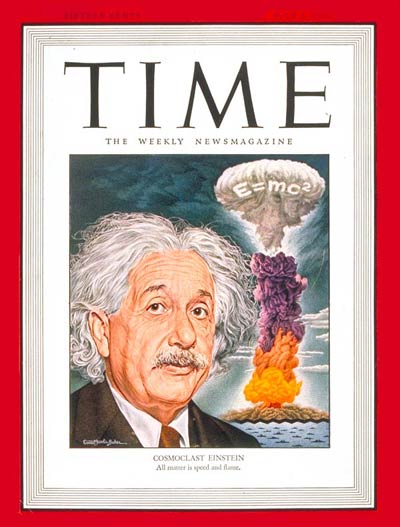

By contrast, Albert Einstein attracted the publicists. In a classic example of media distortion, Time Magazine’s cover story of July 1, 1946 showed Einstein’s unruly mane and his equation E=mc2 superimposed on the mushroom cloud, associating his genius with Hiroshima in the minds of generations to follow. Though it is true that the famous equation did ultimately give an explanation for the large amounts of energy released by nuclear reactions, Einstein’s theory, Special Relativity was definitely not an important factor in the development of the atomic bomb. Even the public’s perception of Einstein’s role in preparing the famous letter to President Roosevelt is false. He merely signed what Leo Szilard had drafted. The entire development of fission was led by experimentalists concerned with radioactivity. A continuous link can be traced from Becquerel and the Curies through Rutherford to Fermi and the horde at Los Alamos.

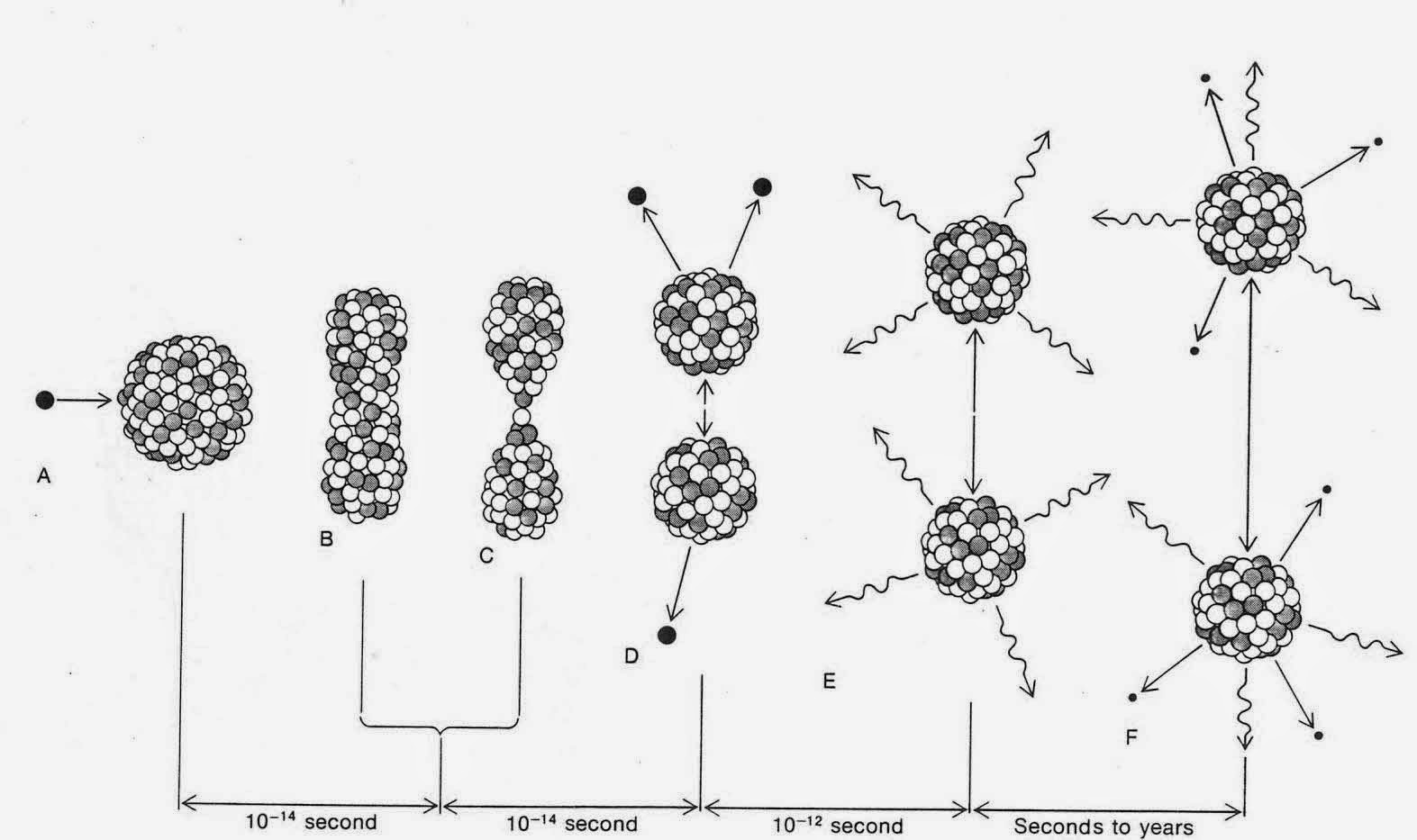

There are many other reasons why Fermi is little-known when the unassuming Einstein, the enigmatic Robert Oppenheimer and the arrogant Hungarian Edward Teller, have become household names. First of all, Fermi did not discover the neutron. It was the meticulous British physicist, James Chadwick, who first demonstrated the independent existence of the particle. In fact, Fermi did not even discover nuclear fission. This great discovery is attributed to the German nuclear scientist Otto Hahn and his assistant Fritz Strassmann, though many other laboratories were very close in 1938, including Fermi’s group in Rome. The Viennese physicist, Lise Meitner and her nephew Otto Frisch gave the first explanation.

What Fermi and his loyal band of colleagues in Rome did discover was that slowed neutrons are better in causing fission and secondary admission, which make the chain reaction possible. Thus, the remarkable and subtle process of nuclear fission, the splitting of the atom, was made possible by slowing down the neutrons. This discovery became the basis for two of the most significant technological innovations of modern times . . . the atomic bomb and the nuclear reactor. Fermi was in the vanguard of both these projects and in the latter case, led the project almost single-handedly.

The reader may well be wondering at this point whether Fermi should be considered a hero or a villain, given the disastrous problems society has had with these two developments. Yet for me, he is clearly a hero and deserves to be appreciated outside the parochial confines of the scientific community. His greatness stems from an unrelenting drive to understand everything and his inspired gift for creative, practical tests of new ideas. Furthermore, in a field where a high degree of specialisation was the norm, Fermi made no distinction between theoretical and experimental problems and was the authority on both. Emilio Segrè, a member of the Fermi’s pioneering group in Rome and later a distinguished professor at Berkeley, believes Fermi was the last of a vanishing rare breed of physicists to accomplish this. In my view, these traits make him a model for the modern day intellectual.

Oppenheimer may have been more profound, Einstein more original and Niels Bohr certainly more politically aware. But none of these was as willing as Fermi to share his brilliance, to take on any problem brought to him, to roll up his sleeves and tackle the myriad questions of students, theoreticians, experimentalists or governments during the heady pre and post-war days of nuclear physics. In addition, his generosity and fairness to colleagues, his humanitarian concerns and his role in the great Italian family tradition make him a role model over again. Lastly, his almost pathological modesty endeared him to all who lived and worked within his orbit.

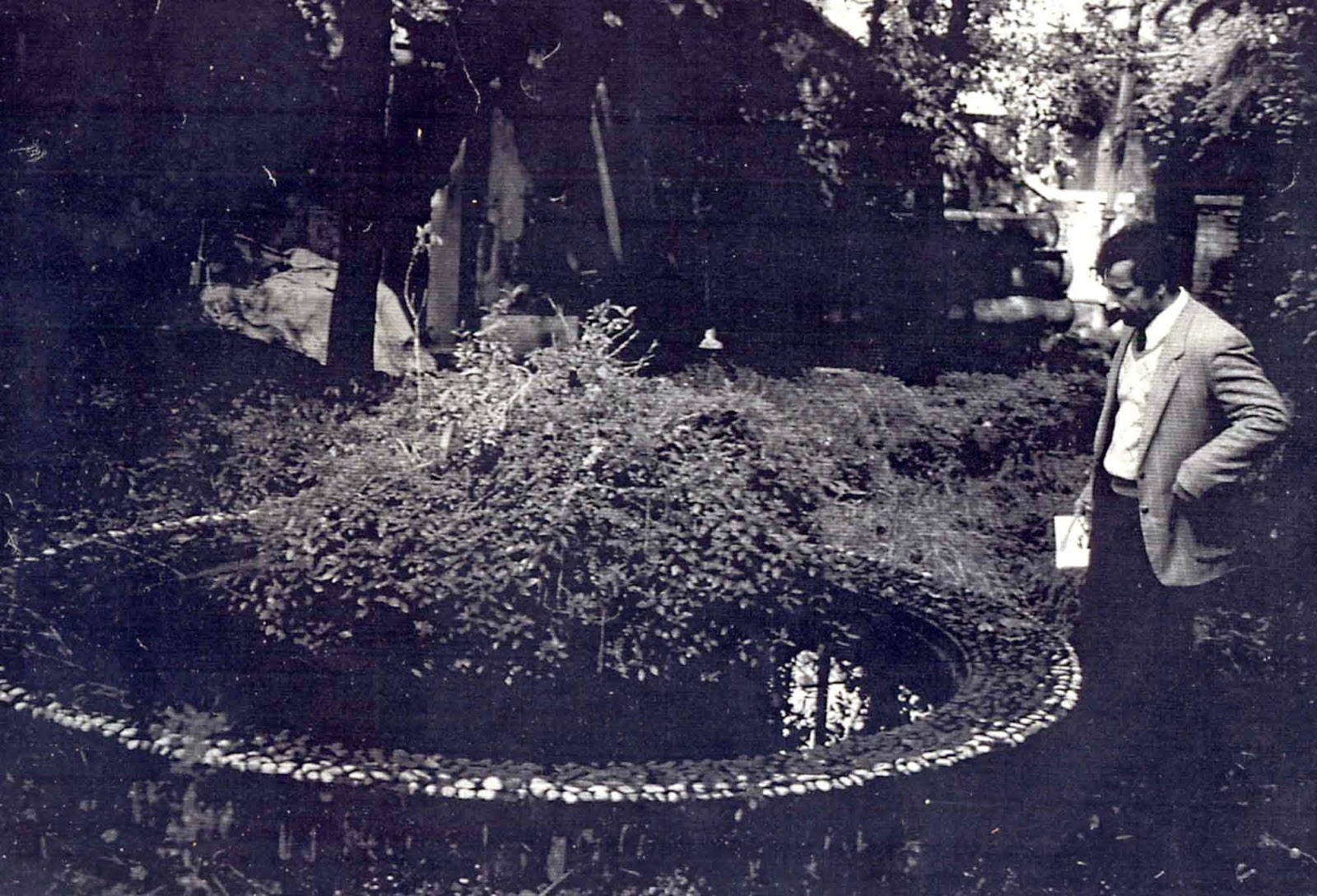

One of the many legendary stories told about Fermi inspired me to visit Rome several years ago. I hoped to find traces of a certain artefact remaining from his tenure there in the 1930s – a fountain. It seems that soon after he realised neutrons could be slowed dramatically by collisions with other particles of unit mass (such as hydrogen atoms), he surrounded the sample with paraffin and saw an increase in the radioactivity. But then in an inspired impulse, he took his entire apparatus from the laboratory into the courtyard of the university and submerged it in a pool of water (H2O) surrounding a small fountain there. The Geiger counter suddenly went berserk, demonstrating dramatically that water could be used as a moderator in neutron-induced collisions. Subsequently, this has been proven to be true and is used in modern nuclear reactors, one of a series of creative, intuitive hunches with which Fermi dazzled his contemporaries.

Arriving in Rome on a warm, sunny day, I set out to see if I could find the courtyard and maybe even the fountain. After all, others go to Rome to see fountains. All I had was a photograph taken in the 1930s showing the University of Rome on Via Panisperna. I easily found the street and the building, helped by the large palm trees in the photo which were still there. Alas, the university had moved many years before, the war causing major disruption in the city. The buildings were now occupied by Italian government agencies and completely off-limits to a passersby. A security clearance was required even to enter the precinct.

I decided to give it my best shot and talk my way in. I tried everything: my US passport, documents showing my credentials as a genuine scholar, papers and photos of Fermi. I even explained that my wife was of Italian descent, which almost did it. Fermi, I said, dove ha funzionato? Nothing. My Italian was poor, their English was worse. But I wouldn’t leave, waiting for the Italian simpatico to take over. Finally, a shy middle-aged man was brought in . . . Signor Albanese. He seemed to know what I wanted. The clearance was arranged easily after I filled out some forms and a plastic badge was clipped onto my jacket.

We walked through several doorways, then along endless corridors, peopled by functionaries carrying stacks of paper and cups of espresso. Are you a journalist? Er, yes. I said. The International Tribune. Thinking perhaps the IHT would print a story if I wrote one about my visit. Finally, Albanese opened another door and stopped . . . gently nodding for me to enter. Along the hallway were several rooms all converted to modern offices. No plaques on the wall, no photos, no evidence of the pioneering work in physics done here in the 1930s. At the end of the corridor was a doorway leading out to a courtyard. My heart skipped a beat as I spotted a small fountain. Signor Albanese seemed puzzled but said he would leave me for ten minutes.

I walked into the courtyard and sat on the edge of the fountain, transfixed. I thought for a moment that this object belonged in the Smithsonian Institute. Now completely overgrown with flowers and vines, the fountain had a special kind of beauty one only finds in neglected Italian gardens. I reached down through the stagnant water into the earth that filled the inner space of the pool. Statistically, it is almost certain that at least a few of the atoms from Fermi’s apparatus were still there emitting radioactive particles. Perhaps some were passing through my arm at that very moment.

Suddenly, I knew my pilgrimage was over. I had made contact with Fermi and the euphoria of that day – 22nd of October, 1934 – when the Italian navigator began his epic journey, a journey that would take him to the squash court in Chicago in December 1942 for the first controlled nuclear reaction and to the sand flats of Alamogordo in July 1945, for the first uncontrolled nuclear explosion. A new age had begun.

Dear Joe – very much enjoying your blog -best wishes – sam

Sam,

Glad to know the cognoscenti are involved.

Joe

Fascinating!!,kudos to the author. I appreciate your intellectual curiosity! I have felt the same way about meeting some of the greats in my field. Grazie mille ted

Joe, this is a wonderful piece! I enjoyed reading it so much that I missed my bus stop. Especially love the ending. Thanks for sharing your life with all.

Maryann,

My pleasure to be doing so.

Joe

http://www.eps.org/blogpost/751263/143790/Enrico-Fermi-fountain-designated-EPS-Historic-Site

Maryann,

Well, I’ll be damned! I knew nothing about this. What a good scout are you.

It’s a good thing my blog is accurate . . . though I’m not sure I got Signor Albanese’s name correct.

Thanks for the heads up.

Joe

P.S. I guess it did end up in the ‘Smithsonian’ after all.

Thanks for adding the photos. Another brilliant piece by my favorite writer. Love, Bob

Fermi is my man!

BTW, great piece on Rome in Saturday’s INYT.

Dig it.

Joe

Same post as yesterday with illustrations